SUBORDER HAPLORHINI

INFRAORDER PLATYRRHINI

NEW WORLD MONKEYS

Called platyrrhines because their nostrils are far apart, wide open and face outwards, South American monkeys are also distinguished by long, well-developed tails. In some groups, the tails are prehensile with a sensitive pad on the tip and serve as a fifth limb. Their big toes are large and strongly opposable but their thumbs are imperfectly opposable and their fingers cannot grip well. New World monkeys belong to two families: the family Callitrichidae, the very small marmosets and tamarins, and the family Cebidae, a diverse group of large monkeys.

SKULLS AND DENTITION

|

1. Skull of Marmoset 2. Skull of Howler monkey |

FAMILY CALLITRICHIDAE

The colourful marmosets and tamarins are easily recognised by their diminutive size, diversely coloured coats and a wide range of tufts, manes and crests. They are unusual monkeys in that they normally give birth to twins, all their digits end in a sharp claw with the exception of the first toe which has a nail and they are the only monkeys to have reduced their dentition by the loss of molar teeth. Callitrichids are highly adapted to an arboreal existence: their small size and sharp claws enable them to cling to vertical trunks and branches and run up the sheer sides of the trees in which they live.

Marmosets and tamarins have varied diets of fruit, leaves, buds, flowers, nectar, insects, spiders, frogs, snails and lizards. They also eat saps and gum. Marmosets are particularly well adapted for this: they anchor their upper incisors into the bark of the trees and make holes for the gum to seep out by gouging upwards with the lower incisors. They then lick up the small droplets of gum and sap with their tongues. The ability to eat and digest gum is useful in times when other food stuffs are in short supply and allows certain species to survive in harsh environments.

All species of marmosets and tamarins are diurnal and strongly territorial. They live mostly in groups comprising monogamous breeding pairs and their offspring.

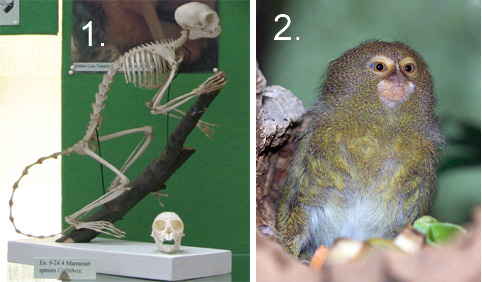

1. Marmoset skeleton

2. Pygmy marmoset. Photograph courtesy of Alan R. Thomson, copyright The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland

FAMILY CEBIDAE

The family Cebidae is an extremely diverse group comprising an enormous array of morphological types adapted to a wide range of arboreal, ecological niches in the tropical and subtropical evergreen forests of South America. Cebids exhibit a range of social structures from monogamous pairs to large polygamous groups. The family Cebidae can be divided into four different ecological groups according to their diets. Spider and woolly monkeys range widely feeding on a mixed diet of fruit and leaf shoots. Howler monkeys are large, leaf eating monkeys capable of digesting a coarse diet of leaves with the aid of a specially extended caecum. Capuchins eat fruit and other species eat seeds.

Spider monkeys have long arms, very mobile shoulder joints and a very flexible prehensile tail which serves as a fifth limb. Using their long arms, they swing over hand below the branches using their tails to grab branches for safety if needed. They also reach food by hanging from their tails. Cebids have finger nails instead of claws.

Ateles paniscus, the black spider monkey. The typical face and prehensile tail of platyrhine monkeys are shown by this stuffed spider monkey.

Howler monkeys live in troops which have a dominance hierarchy so that low troops avoid high troops. The males use their calls to advertise the presence of a troop and possibly to defend a troop’s right to particular food trees. Male howler monkeys produce some of the loudest calls made by animals with howls travelling up to a kilometre. When the male howls, he passes air through the cavity in the enlarged hyoid bone that supports the larynx in his throat. A male’s hyoid bone is much larger than a female’s hyoid bone. Using calls instead of the physical movements involved in patrolling boundaries, displays or fighting saves energy.

1. Front view of skulls of Red Howler Monkey, Alouatta seniculus, female (left) and male (right).

2. Rear view shows the large hyoid bone used for howling.

3. Side view shows the deep lower jaw typical of platyrhines.

Howler monkeys need to save energy because they mostly feed on leaves. As leaf eaters, howler monkeys can find food more easily than monkeys that feed on fruit, flowers and insects, but leaves are more difficult to digest and provide less energy than other food stuffs. Leaves are very low in sugar, which is an important energy source, and low in nutrients relative to indigestible fibre. Howler monkeys can live on a diet of leaves because they possess two large sections of hindgut – the caecum and the colon – where cellulose is digested by bacterial fermentation. In addition, they tend to feed on young tender leaves, as these are more rapidly fermented, and on sugary fruits and flowers when available.

As well as the male conserving energy by using calls to advertise his troop’s presence, howler monkeys conserve energy by moving slowly, spending half of their time resting or asleep, and by employing a division of labour whereby males settle disputes and defend food trees and females reproduce and care for the young.