SUBORDER HAPLORHINI

INFRAORDER CATARRHINI

SUPERFAMILY HOMINOIDEA

APES AND HUMANS

Apes are grouped together with Old World monkeys in the infra-order Catarrhini because their nostrils are narrow and close together. The name catarrhine literally means ‘drooping nose’. Within the infraorder Catarrhini, apes and humans are assigned to two families in the superfamily Hominoidea.

While apes occur only in tropical or subtropical regions of the Old World, namely Africa and Asia, humans live in all regions of the world. As so much information about apes and humans is readily and easily available from other sources, including the World Wide Web, this page on apes has been planned only to illustrate our ape skulls and skeletons so they can be compared to the skulls and skeletons of the other animals in our Collections. |

|

HOMINOID STRUCTURE

|

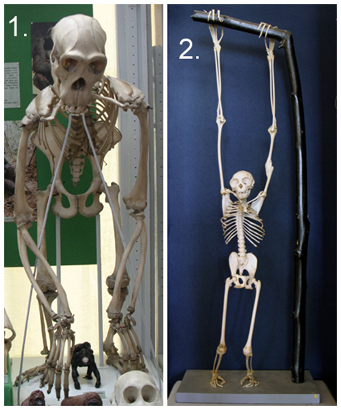

As the skeleton of a chimpanzee (1) and gibbon (2) to the right show, apes have short backs with wide, barrel-shaped chests and robust pelvic girdles. The length of spine between rib cage and pelvis is much shorter in apes than in monkeys. These features are related to the upright posture of their bodies. The development of a vertical posture in apes was accompanied by increased manual dexterity. Apes’ fore limbs are longer than their hind limbs (except for humans). Apes have extremely flexible shoulders, elbows and wrists. The two bones (ulna and radius) in the lower fore limb and the two bones (tibia and fibula) in lower hind limb of apes are separate and highly mobile. All apes lack tails as they are not needed for balancing. |  |

SKULLS

The characteristic appearance of the heads and faces of the different apes and humans reflects the different shapes of their skulls.

Apes' skulls have flattened faces with complete and forward pointing bony sockets for the eye – a plate of bone separates the orbit from the jaw muscle. The frontal bones are fused at the midline. The foramen magnum, the opening in the base of the cranium where the spinal cord goes into the vertebral column, is ventrally placed underneath the skull. This arrangement allows the eyes to face forward when the body is upright.

Photograph of buff cheeked gibbon courtesy of Alan R. Thomson, copyright The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland.

1. Skull of Hylobates hoolock, white-browed or hoolock gibbon, from South East Asia – Bangladesh, Burma, Assam.

2. Skull of Pongo pygmaeus, the Bornean orang-utan.

3. Skulls of male and female Gorilla gorilla, the Western gorilla, from Equatorial Africa.

4. Skull of Pan troglodytes, the common chimpanzee, from West and Central Africa.

5. Skulls of Homo sapiens, a human being; one skull prepared to show brain case.

Gibbon skulls (1) are relatively light and there is little difference in the skulls of males and females, they have the largest canines, relatively speaking, of all apes.

The skulls of the heavier great apes and humans (2-5) are robust to protect the brain from damage.

Orang utan skulls (2) slope markedly backwards, unlike the skulls of gorillas (3) and chimpanzees (4).

The skulls of male gorillas (3) and orang utans are much more heavily built than the females and also have substantial midline (sagittal) and neck (nuchal) crests to provide additional attachment surfaces for neck muscles.

The human cranium (5) is smooth-domed and lacks crests; the brain cavity is very large.

The skull of the chimpanzee (4) is very like a human skull .

DENTITION

|

Apes have relatively well developed jaws: the lower jaw is fairly deep and the two halves are fused in the front. The dental formula is the same as Old World Monkeys: I2/2; C1/1; P2/2; M3/3 = 32. The teeth include spatulate (shovel-shaped) incisors and prominent canines; the rear edge of the upper canine hones against the front edge of the first lower premolars. The molars have 5 cusps and a complex arrangement of ridges on their grinding surfaces. The presence of squared off cheek teeth reflects the predominance of plant food in the diet. Used together, these teeth enable most apes and humans to process a variety of vegetarian food stuffs. Apes have greatly developed canines with sharp blades, which hone against the modified shearing edge of the first lower premolar tooth, and may be used as weapons. The human canine tooth is not as good a weapon. |  |

LOCOMOTION AND MANUAL DEXTERITY OF APES AND HUMANS

|

Different ape species move in different ways. Gibbons and orang-utans swing under-arm from branch to branch by their very long fore arms; gibbons also walk upright on their hind limbs. Brachiating - swinging by the arms - leaves the feet free to carry food. Chimpanzees and gorillas move on all fours using the knuckles of the fore hands for support. Humans walk vertically on their hind feet. Both hands and feet of apes help to support the body and both are used for climbing and manipulating objects. In humans, the acquisition of a vertical posture and a bipedal gait, using only the hind limbs and feet to progress, has been accompanied by an enhanced manual dexterity due to increased mobility and opposability in the fingers and thumbs. |  |

|

1. Skeleton of Hylobates sp. Gibbons are adapted to brachiate – to swing suspended underarm from branch to branch. They have long arms, short legs, extremely mobile shoulders and hands with long fingers to hook over branches. This preparation shows how they use their hands to hook onto a branch; their reduced thumbs do not get in the way of the fingers. As gibbons hold onto a branch with their long arms, the body swings like a pendulum about a fixed point and the animals gain the momentum to carry them through the air to the next branch. Their upright posture and strong pelvis enables them to run along branches, which are too thick to hook onto and swing from. Photograph of buff cheeked gibbon courtesy of Alan R. Thomson, copyright The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland. |  |

|

2. Skeleton of Pan troglodytes, the common chimpanzee. A chimpanzee’s structure enables it to climb trees and to move over the ground on all fours using the knuckles of the fore hands for support. This preparation shows the short back with wide, barrel-shaped chest, robust pelvic girdle, short length of spine between ribs and pelvis that enable chimpanzees to assume a more upright posture than the monkeys illustrated elsewhere. The way the skeleton is mounted shows how a chimpanzee’s hands could reach the ground and help the feet support the moving body. The radius, the rotating bone in the lower fore arm, has a special ridge where it meets the knuckles which prevents the knuckles buckling under the animal’s weight. This type of skeleton is also well adapted to an arboreal existence. The long fore arms, reaching to below the knee when the animal stands, large hands with opposable thumbs and large feet with rasping big toes help the animals to climb, hang from branches, feed and make nests for sleeping at night in trees. Their hands can process their food and employ sticks as tools. |  |