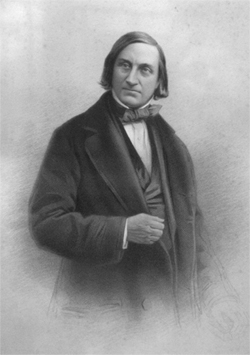

EDWARD FORBES (1815 – 1854)

FORBES AS SCIENTISTThe great malacologist Edward Forbes was both student and Professor of Natural History in the University of Edinburgh. On the anniversary of his death, James Ritchie, Professor of Natural History (1936 – 1952) wrote: ‘ Edward Forbes was lovable, a loyal friend, and above all he had the energy and initiative to make, in his short life, contributions to each of botany, zoology, geology and paleontology, and to the blending of these far-reaching truths, such as no other man of his time could have encompassed.’ Of Forbes’ marine studies, Ritchie wrote: ‘Forbes laid the foundation of a branch of knowledge, then undefined, which one of his successors in the Edinburgh Chair of Natural History, Sir Wyville Thomson firmly established - the science of Oceanography.’ Forbes’ most famous written ‘Zoological’ works include: History of British Starfishes and other Animals ofthe Class Echinodermata (1841) and History of British Mollusca and their Shells. 4 vols. (1848-1852) written with W.E. Hanley.  |

|

FORBES AS ARTIST AND HUMORIST

Forbes extraordinary sense of humour and his talent as an artist and poet are revealed by the verses and drawings with which he illustrated his zoological treatises. His drawings clearly show his sympathy for the animals he studied. Forbes was also founder member of three societies: The Maga Club, a student club dedicated to literature and good fellowship; The Universal Brotherhood of Friends of the Truth, whose watchword was ‘wine, love, learning’; The Red Lions, a dining club for younger members of the British Association, named after the tavern where the first meeting was held.

FORBES AND JOHN GOODSIRGiekle and Wilson, Forbes’ biographers recorded how Forbes and John Goodsir, the anatomist, became friends while still medical students. On Goodsir’s first visit to Forbes’ lodgings ‘ he found his new friend with a snail which Forbes had boiled with a view to studying its structure. Mr Goodsir advised the omission of boiling and gave the future great malacologist his first lesson on dissecting mollusca.’ Forbes and Goodsir were devoted friends and scientific colleagues. Together they studied such diverse animals as Amphioxus, echinoderms, sipunculids and echiurids. It would be nice to think that the 6-foot long sunfish described by Goodsir as lying sluggishly on one side, in shallow water off Culross, but making vigorous resistancewhen attacked was the same sunfish as the one painted by Forbes.  |

|

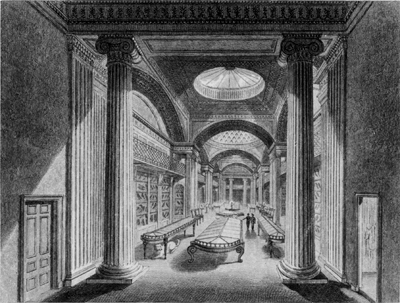

FORBES AND THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM

On succeeding his mentor, Robert Jameson, as Professor of Natural History in 1854, Forbes wrote: ‘I find Jameson’s collection wonderful but it is arrayed more with a view to the artistic than to scientific order.’ He then addressed himself to the thorough remodelling of the collection. He arranged the Upper Gallery to demonstrate the major divisions of the Animal Kingdom from Protozoa to Mammalia and illustrated the exhibits with his own sketches. He held that the Museum and class were inseparable and also arranged selected examples of genera relating to the previous day’s lecture in a special ‘table case’ so that students could examine them in detail. It was Forbes’ belief that the Natural History School and Museum in Edinburgh might be the first in the world for educational purposes. Sadly he died after only seven months as Professor.

The Royal Museum of the University (now Talbot Rice Art Gallery), Old College, University of Edinburgh.