BIRD SKELETONS AND SKULLS

Bird skeletons are modified so that birds can fly as well as balance and walk on their hind limbs. They are light and compact for maneuverability with most weight near the centre of gravity. Their bones are reduced in number and hollow, some lightened by air sacs; many bones are fused into a rigid frame to hold the bird together. Since their wings are committed to flight and their hind limbs to locomotion, birds' beaks evolved into highly specialised tools for catching and handling food, preening and building nests.

SKELETONS, FLIGHT AND WALKING

Modifications of the basic skeletal plan have enabled birds to adapt to a wide range of habitats and life styles and exploit diverse sources of foods.

1. Flamingos (O. Ciconiiformes) have long legs for wading in soda lakes. The bill is held upside down in the water and the tongue acts as a piston moving water in, then out through a horny sieve to trap algae and invertebrates. The young feed on 'milk' from the adults' crops until their bills are hooked and they can feed themselves. |  |

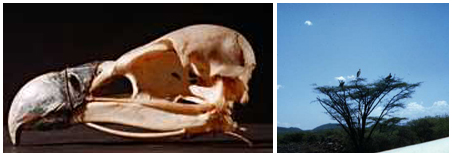

2. Parrots (O. Psittaciformes) live in trees on seeds and fruits. Their characteristic and adaptable bill can preen, crack open nuts and seeds and help as a grappling hook for climbing. A special hinge between the bill and skull gives great mobility and leverage. Their feet make them the most manually dexterous of all birds and can be used to manipulate things close to the bill. Budgerigars are nomadic, flying long distances in search of food. |  |

3. Owls (O. Strigiformes) hunt their prey in darkness using sight and sound. Oversized skulls house very large ear openings and eyes, frontally-placed for binocular vision. Flexible necks allow them to look directly behind. Their hearing is exceptional; the stiff feathers of their mobile facial disks help channel sounds into the ears. Short hooked beaks tear flesh. Powerful legs with sharp curved talons grip the prey; outer toes point both ways for a better grip. |  |

4. Herons (O. Ciconiiformes) are highly specialized predators capturing live fish, amphibians and insects. They wade through water and mud on their long legs to stalk their prey, which they catch with a rapid stab of a sharp pointed bill. |  |

5. Pigeons and doves (O. Columbiformes) have a non-specialised body form, skeleton and skull. Strong fliers, they dwell and roost in trees. They feed on seeds, fruits, flowers, leaves, buds and small invertebrates. |  |

6. Penguins (O. Sphenisciformes) like the Jackass penguin, Spheniscus demersus, cannot fly as their wings are strong, stiff and narrow. They feed on crustaceans, fish and squid, caught and swallowed under water. Their streamlined bodies and flippers enable them to swim and dive rapidly. Their short legs, webbed feet and tail act as rudders. They only waddle slowly on their short legs, but move about rapidly on ice by tobogganing on their bellies. |  |

7. Hawks (O. Falconiformes) are predators with acute vision for finding food and with strong legs, sharp claws and a hooked beak for holding and tearing apart the bodies of other animals. |  |

SKULLS AND FEEDING STRATEGIES

Several beaks from large birds show how beaks have evolved to tackle different kinds of foods.

Vultures (O. Falconiformes) are carrion feeders with sharp hooked beaks for tearing apart the flesh of other dead animals. |  |

Gannets (O. Pelecaniformes) are adapted for plunge-diving and catching fish underwater. They have a tapered body, long wings and tail and shock-absorbing air sacs. Their bills are long with a sharp point and serrations on the cutting edge; their nostrils are occluded. |  |

Pelicans (O. Pelecaniformes) feed communally by herding schools of fish and scooping them up synchronously in their pouched bills, which serve as dip nets. |  |

Albatrosses (O. Procellariiformes) use their strong beaks to seize their prey - mainly fish, squid and crustaceans - from the sea’s surface. They are adapted to glide for long distances over the windswept Southern oceans that encircle Antartica. |  |

A pair of Royal Albatrosses, Diomedea epomophora, on their nest (copyright: The Department of Conservation, New Zealand.)